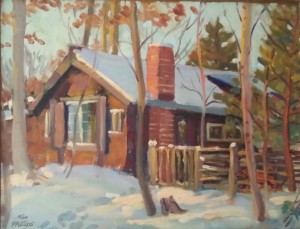

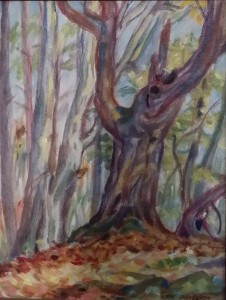

One of Ken’s frames, for a painting by his wife. Note the decorative combing texture in the upper corners

The frames my father designed and made to enhance my parents’ pictures were a passion in themselves. As a teenager, occasionally I was enlisted with my sister to help in this complex, exciting process. These frames came about mainly because my parents couldn’t afford ready-made frames of a quality my father deemed necessary. Rather than seeing this as a chore, though, in his characteristic way, he poured thought and skill into them. I already saw my artist father as an alchemist, with his occasional cooking of vile-smelling rabbit’s foot glue on a hot plate, or the mysterious mixing of linseed oil and oil paint which brought my world to life. But it was with his frames, where he transformed the most ordinary wood that I could see his art in action.

Sometimes he bought simple frames, as in the example above, treating them until he thought they did justice to the pictures they were designed for. Later, he snapped up discarded old ornately sculpted and gilded frames or ones of handsome fruitwood from Toronto second hand stores. He hunted through books of antique techniques, and fabricated strange tools, taking over pieces of comb with which he made dragging, wavy lines in half-set gesso. Sometimes he had my sister and me distress plain wood with nail holes, in which he trickled India ink to imitate worm holes.

Most magical was the process of burnishing gold leaf, though even my father seemed scandalized by the expense of this technique. In the many steps of this process, first he covered the frame with a base, which he coated with an terra cotta color. This, in turn he wiped with a rag, to create an irregular effect. Next he flipped through his little books, selecting delicate sheets of copper, silver or even precious gold, almost light as air itself. I watched as he took his agate burnisher, a tool made of a real, semi-precious stone, and polished until the leaves mysteriously melded onto the frame. After this, after turning his creation thoughtfully between his fingers, he might have second thoughts about the rawness of the new color, in which case he might take up a rag to soften the effect with an uneven rubbing of thin white paint.

“People don’t appreciate them,” my mother sometimes protested, exasperated by the good painting time he devoted to his creations. Eventually, age and the suspicion that he was indeed casting pearls to swine, would force him to abandon such elaborate procedures. It was about this time that he turned to buying mouldings from which he constructed much simpler, if less charming, frames.

She tested the climate with Margot, a life-sized portrait of her sister, in a softly ruffled dress baring her shoulder, and with her eyes provocatively downcast, which was exhibited in the spring 1934 O.S.A. show. The following autumn, the R.C.A. show included two life-sized works by Marie. Once my mother had been a frail little girl who dreamed and poured over her books of tales and legends. Now, in 1934, she painted her blonde classmate, Isabelle Dawson (later to become a successful New York illustrator), in a similarly dreamy pose looking at the book Tales of Long Ago and waiting for her lover to come and call. [illust – Once Upon a Time] Harking back to the magical 1929 O.C.A. masquerade ball on the theme “King Arthur’s Court”, where both my parents had been praised by the press for the originality of their costumes, Marie made up a background tapestry effect for this portrait. Subsequent to the R.C.A. show, this painting was exhibited across Canada. Although she was just twenty-six, author and critic Kenneth Wells, reviewing Once Upon a Time, remarked: “This lady is making rapid strides towards the front rank of figure painting.”

She tested the climate with Margot, a life-sized portrait of her sister, in a softly ruffled dress baring her shoulder, and with her eyes provocatively downcast, which was exhibited in the spring 1934 O.S.A. show. The following autumn, the R.C.A. show included two life-sized works by Marie. Once my mother had been a frail little girl who dreamed and poured over her books of tales and legends. Now, in 1934, she painted her blonde classmate, Isabelle Dawson (later to become a successful New York illustrator), in a similarly dreamy pose looking at the book Tales of Long Ago and waiting for her lover to come and call. [illust – Once Upon a Time] Harking back to the magical 1929 O.C.A. masquerade ball on the theme “King Arthur’s Court”, where both my parents had been praised by the press for the originality of their costumes, Marie made up a background tapestry effect for this portrait. Subsequent to the R.C.A. show, this painting was exhibited across Canada. Although she was just twenty-six, author and critic Kenneth Wells, reviewing Once Upon a Time, remarked: “This lady is making rapid strides towards the front rank of figure painting.”