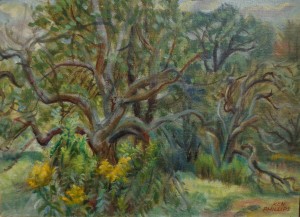

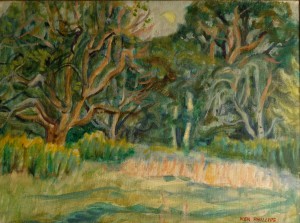

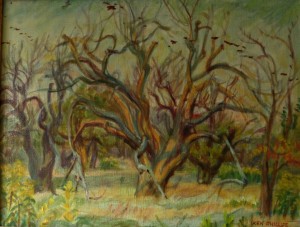

Ontario Farmhouse – Marie Cecilia Guard

Reflecting about her art near the end of a long life, my mother, Marie Cecilia Guard, wrote a journal entry which might have provided her epitaph: “My subject is color and light giving joy.” She truly lived a lifetime devoted to art. With every spare moment she could steal from a life of poverty, ill health and family obligations, she was painting, drawing, and studying. But the cost was very high.

Quite simply, being a woman artist in her generation meant walking away from the crowd. Upon graduation in the thirties, many of her woman friends from the College of Art married and largely abandoned their artistic dreams. Her two best friends, Annora Brown and Euphemia (Betty) McNaught returned to Alberta, where they painted and taught art all their long lives. But, unlike my mother, they did not take on the distractions of marriage and children.

For much of her adult life, in spite of her great love affair with my father, Ken Phillips, Marie suffered from profound loneliness. Moving to Mississauga from Toronto just before World War II and its ensuing gas rationing, inevitably meant that she and Ken largely severed their art connections. Her middle class neighbors in Mississauga found nothing in common with the beautiful artist, and she, in turn, recoiled from stultifying coffee parties, where conversation centered on washing machines and new recipes. When neighborhood children were invited to my birthday party, and it was

discovered that the art on the walls of our home included large pictures of unclothed women, our family became permanently branded as suspect.

In the fifties and early sixties, when my mother taught would-be artists in Port Credit, she faced another, but equally unfortunate, kind of distancing. In awe of her ability and knowledge, her students were friendly, but, as students often do, they mainly kept their teacher at arm’s length.

In terms of promoting her art, my mother was hampered by old-fashioned notions. The dreadful accusation of “not nice” often rose to thwart her. “It was not nice to promote your own work.” What was “nice” was cherishing the improbable dream that at long last someone would discover how gifted you were and would take up your cause for you. Isolated as she was, she lacked the confidence to “put herself forward” in the competitive post-war art world.

And yet, my mother never, ever gave up on what mattered most to her. The hand-sized homemade sketch pads my father crafted sat ready wherever in the house she might be. I remember her pausing from stirring soup to capture a chickadee in the pines outside the window. Still lifes were arranged in the Studio, where giant easels loomed, were waiting to be captured in oil. There are sheets of sketches of her daughters as babies. Marie had merely to glimpse a gleam of sun striking from clouds, and she whipped out her pencil crayons to capture the evanescent light, making notations for a later

picture. In late life, coming out of an anesthetic after hip surgery, her first request was for paper and pen. Doctors and nurses gathered in amazement as she captured a likeness of the hundred year old woman in the bed beside hers. In spite of macular degeneration and cataracts, a large table in her retirement home room was spread with masses of color studies which she continued nearly until her final, devastating stroke.

“My subject is color and light giving joy.” To this I would add that her gift was to see and convey Gerard Manley Hopkins’ “There lives the dearest freshness deep down things.”

“My subject is color and light giving joy.” To this I would add that her gift was to see and convey Gerard Manley Hopkins’ “There lives the dearest freshness deep down things.”