Recently, I was given a gift when professional artist and teacher David Wick contacted me to share some memories of long ago days when he experienced my artist father’s daily train trips to and from his work in Simpsons art department in Toronto. His words brought back my father’s zeal and devotion to his art, so, with his permission, I’ll let David speak for himself about the times when he and his friend Reid also were commuting to study art in Toronto and when they experienced my father’s passionate commitment.

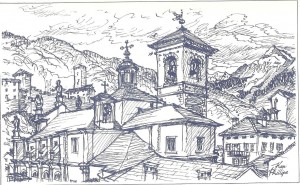

…your father always found his window where he’d begin his drawings,..incessant drawings of so many things,..people and subjects that grabbed his thought and mind en route.

Reid and I just watched his hands flowed over each drawing with his magic pen,…a fountain pen with black ink and chiseled nib drawing and drawing moving to some hidden inner rhythm your father knew instinctively and with such interest in every object that captured his eye and heart.

Your father Ken would draw and talk little if either Reid or myself asked questions while we rode the train,…and sometimes Ken would enter this “zone” and his hand did all the talking …a blaze of movement back and forth capturing the gestures of people on the outside of the train walking with their bikes,..parking them or others in conversation at the train stops on the platforms, even people next to some buildings talking or moving into some space,..he seemed to be perpetually drawing and sketching. That chisel nib must have had it’s well past it’s replacement date,..or at least it’s warranty deadline!

***

Your Fathers grey suit,..with his bike sprocket protector about his ankle and wrinkled pant legs showed Reid and Me that drawing was his absolute love, and devotional focus, not his pants. Every once in awhile,..he’d look up but only to turn the page on his clipped paper pad or pile of drawing papers he’d combined to make into a drawing pad and turn them over as the journey progressed. The drawings where never large,..but smallish,..about 8″x10″ or so, that he seemed to carry with him everywhere. … When he did look up at us,…it was as though he was questioning what we where looking at,..he was simply lost in his drawing and referencing the everyday gathering of travellers and bystanders en route to Toronto. He simply lived for drawing!

At this point I replied to David with some memories of my own:

He was an ardent teacher and could hardly help telling people about his passion, often more than they wanted to hear. If he didn’t talk with you, two appreciative young men, I’m thinking it was because by five pm he was exhausted, having been up since five am. Only by clinging to his art after a day of sketching things like mattresses, could he survive by turning to subjects like clouds. His little cobbled-together pads and yellow thick lead pencils were designed to fit in the palm of his upturned hand so he could do caricatures without being noticed.

David replied:

Yes,…I do remember your father sketching with pencil in hand, and indeed they where stubs he’d sharpened with his penknife as they looked revealed by that procedure. When I mentioned your father going silent from time to time when we talked with him,..it was because he appeared lost in his wonder at what he was drawing and was caught up away in his enjoyments.

However,…I was always more impressed at your fathers ink sketches as they couldn’t be erased, they where immediately fresh and gestural,…loose yet concise. Reid and I where amazed at his drawing skill level, his perceptions and observations so clear about the subject he was drawing.