Sitting under the rain-spattered roof on a summer day perched reading snatches from piles, occasionally my eyes lifted from the ripe, promising scent of books. For a few moments, I gazed down from my staircase eyrie through the glowing colour of the Venetian lantern into the stage world of the studio below me, with its tall easels and stools, and palettes and pungent turpentine and linseed oil. But then I plunged back into the extraordinary experience of the books of my father’s library.

You might say that books were the furniture of our house. Since my dawn of memory, I moved past living walls of them. They ascended the staircase with its bamboo railing. And eventually they would spill out of the cupboards of my bedroom and onto my big green chair. Also, often at home there were cadences of reading, as one parent or the other shared something of interest, I heard often that my grandparents, and even our long ago ancestors, were devoted readers. And, of course, there were snatches of reading to their small daughter. Really, it was assumed at home that books were meat and drink, just as the Water Rat’s river in The Wind in the Willows was for him.

In the beginning and always there were books. I learned to walk by pulling myself up the shelves of a bookcase. Up and down the book-lined staircase my path to and from bed was marked by books. Handsome bindings, marbled end papers, the secret valuable bound collections of Japanese prints which I wasn’t supposed to touch because the pages were too precious for my childish hands. Before I could read, the heavy books that tumbled off the lower shelves made forts for me or even slides for my miniature cars if no parent was around.

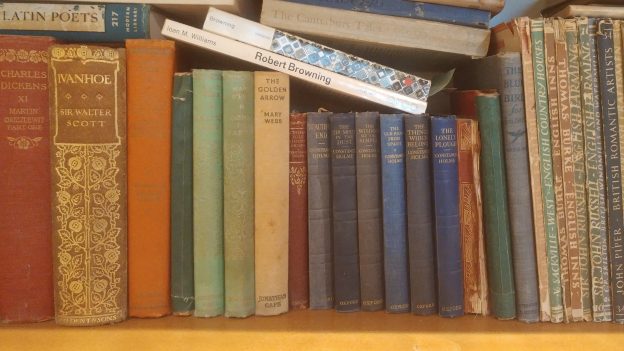

Later, as I was growing older, four or five times a year I applied to him even though I knew it could be risky to involve my quixotic, passionate father. “I haven’t got anything to read,” I said in a whiney, “feed me” sort of voice. The cardinal crime. Right away he dropped whatever he was involved in and we went on an expedition together where I let him pull out twenty or thirty prospects for the sheer pleasure of hearing him sell them to me. (There is a special savour to seeing what books someone else would bring you as opposed to choosing your own.) By this time the books on the home-made shelves were two layers deep, with others crammed on top. The lilting Welshness in his voice became rounder as he lured me with Great Expectations, Tarka the Otter, Two Little Savages, Coming of Age in Samoa, The Bible as Literature, or The Worst Journey in the World, but perhaps not Ecclesiastical Polity.

There was an extraordinary democracy to the books of my father’s library. Learning was profoundly essential to him. Barely a day went by in which my father didn’t bicycle home from work with a shopping bag of books. Second hand books. Nickle and dime books. From them he built it carefully. He built it haphazardly.

Impelled by his urge to make our house into a citadel, the books that spilled out of his bag were blocks in the fortification. My mother’s exasperation grew as he began to bring home not just one copy of Cranford but two or even five. My sister and I would each need a copy to leave home with, he defended himself, fondling a particularly choice crimson leather binding with gilt scrolls. And you never knew which of your friends might need one too. (It was never want: you needed books.) By now one whole wall of their bedroom was books, and still the library was growing.

Only my father knew for sure where the books were in his odd, but fully reasoned, cataloguing system. There were bound National Geographics lettered on spine, Practical Economics, Moll Flanders, Peter Arno’s Cartoons, Noel Coward, The Odyssey, The Iliad, Ibsen, Walden, The Origin of the Earth, Liberty in the Modern State, From Medicine Man to Freud and multiple copies of The Heart is a Lonely Hunter.

I foraged in my own narrower fields, the large illustrated volumes of The Swiss Family Robinson and Robinson Crusoe, or the photography annual with portraits of dogs, or Emily of New Moon, my favourite L. M. Montgomery book, but when my father took me looking for new books, he dove among the shelves, knowing where everything was. On and on we went, with my father drawing out and blowing dust off one book after another.

“Ken!” my mother appealed. It was getting late and she was tired and ready for bed “Coming, Mother”, he said, so deep in pursuit of the ideal book that I knew that there was absolutely no hope of his coming any time soon. A ripe hour later, we descended the stairs, each carrying a chin- high pile of books that I “might like to have a look at.” At the bottom turn of the stairs he wavered and took one hand to draw out one last prize like an arrow from a quiver, “You know, what you really should look at is this…”

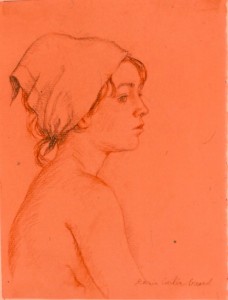

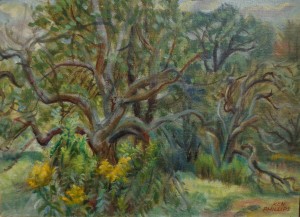

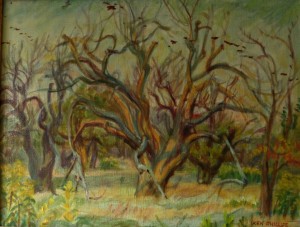

She tested the climate with Margot, a life-sized portrait of her sister, in a softly ruffled dress baring her shoulder, and with her eyes provocatively downcast, which was exhibited in the spring 1934 O.S.A. show. The following autumn, the R.C.A. show included two life-sized works by Marie. Once my mother had been a frail little girl who dreamed and poured over her books of tales and legends. Now, in 1934, she painted her blonde classmate, Isabelle Dawson (later to become a successful New York illustrator), in a similarly dreamy pose looking at the book Tales of Long Ago and waiting for her lover to come and call. [illust – Once Upon a Time] Harking back to the magical 1929 O.C.A. masquerade ball on the theme “King Arthur’s Court”, where both my parents had been praised by the press for the originality of their costumes, Marie made up a background tapestry effect for this portrait. Subsequent to the R.C.A. show, this painting was exhibited across Canada. Although she was just twenty-six, author and critic Kenneth Wells, reviewing Once Upon a Time, remarked: “This lady is making rapid strides towards the front rank of figure painting.”

She tested the climate with Margot, a life-sized portrait of her sister, in a softly ruffled dress baring her shoulder, and with her eyes provocatively downcast, which was exhibited in the spring 1934 O.S.A. show. The following autumn, the R.C.A. show included two life-sized works by Marie. Once my mother had been a frail little girl who dreamed and poured over her books of tales and legends. Now, in 1934, she painted her blonde classmate, Isabelle Dawson (later to become a successful New York illustrator), in a similarly dreamy pose looking at the book Tales of Long Ago and waiting for her lover to come and call. [illust – Once Upon a Time] Harking back to the magical 1929 O.C.A. masquerade ball on the theme “King Arthur’s Court”, where both my parents had been praised by the press for the originality of their costumes, Marie made up a background tapestry effect for this portrait. Subsequent to the R.C.A. show, this painting was exhibited across Canada. Although she was just twenty-six, author and critic Kenneth Wells, reviewing Once Upon a Time, remarked: “This lady is making rapid strides towards the front rank of figure painting.”